TRY THIS: Stand sideways in front of the mirror in a wide second position. Perform four 8-count demi-pliés as slowly as possible without tilting your pelvis and leaning forward. Can you do it?

TRY THIS: Stand sideways in front of the mirror in a wide second position. Perform four 8-count demi-pliés as slowly as possible without tilting your pelvis and leaning forward. Can you do it?

DEMI-PLIÉ WITH STRENGTH & CONTROL

The demi-plié is the preparation for, and the end of, almost every movement we make in ballet dancing. Therefore, it must be done with strength and control. This is the first and most important lesson I teach all students.

Get in front of the mirror and stand in a wide second position (at least two foot-lengths apart). Your body should resemble a triangle. You are going to stretch up through your head with energy that equals what you put into your feet and legs.

I don’t want you to relax into a picture position. Your knees will bend into the plié position because your feet are going to grip the floor and pull your legs.

To get the feeling of this, curl your fingers over each other. Now grip and pull as hard as you can without letting go. Can you feel the muscles in your fingers, hands, arms and shoulders?

Now do this with your feet to make your plié.

Your toes claw and your feet grip the floor, and slowly pulling your legs into the plié. Reach for the ceiling with your head. You should not see an abrupt drop in height or any jerky movements. Your knees are moving outward, but you barely see a downward movement. That’s because the energy you are using to stretch up is equal to the energy you are putting into your feet and legs.

You are stretching up the back of your neck and trying not to bend your knees. You feel a stretch in your hips as your legs move away from each other. You are pulling in your stomach muscles tightly. You are trying to keep your pelvis up.

The almost-isometric plié is hard work! You can feel that all of your muscles are engaged—from your toes through the foot to your ankles, the outside of your lower legs, your knees, your thighs, your hips, up the front of your body and the back of your neck.

It’s not how low you go; it’s HOW you go. What is important is that the plié begins and ends with your toes.

Now change your thoughts. You relax your feet and spread your toes. You are pressing down on the floor with your feet. Slowly, imperceptibly, your legs are in motion, and you realize you are standing as you began, in the triangle position.

The almost-isometric plié is an “invisible” movement. On count 1, you are standing with straight legs, and on count 8, you are in plié, but you never saw the downward movement. The ascending movement is also “invisible.” You are in plié, and eight counts later, you are standing in the triangle, but when did it happen?

Especially at the barre, try to make all of your pliés—large and small, two feet or one foot, slow or fast—almost isometric. Try to do this in center floor as well, tempo permitting. Then you will always have a plié which will enable you to move with strength and control.

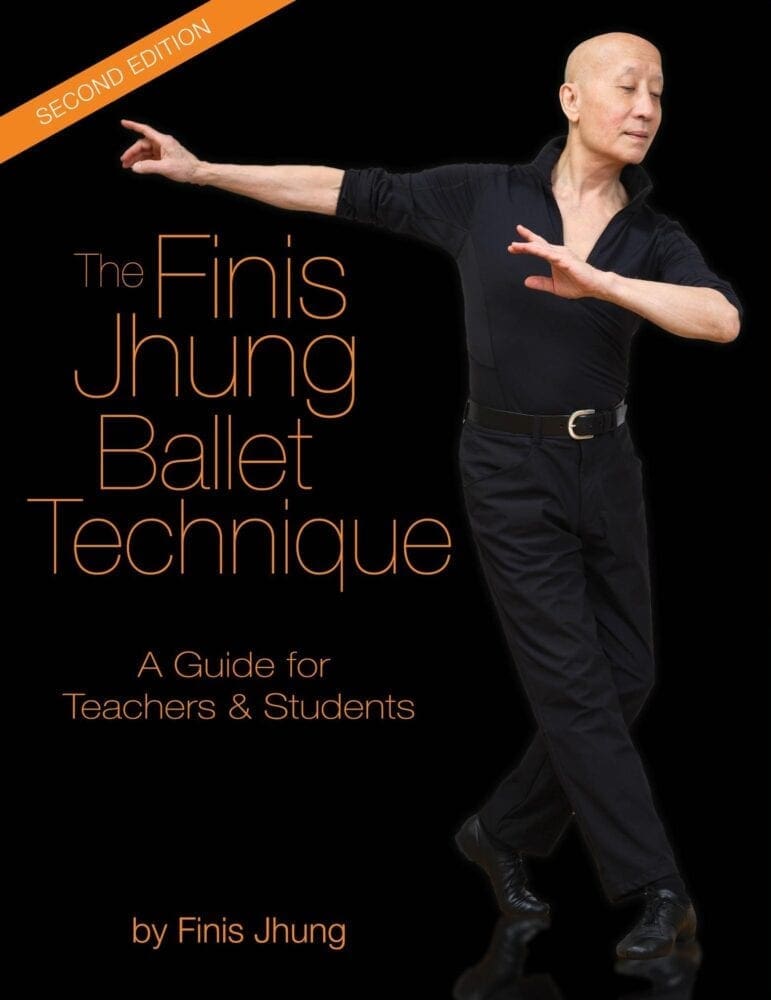

(Excerpted and REVISED from my book The Finis Jhung Ballet Technique: A Guide for Teachers & Students

To learn more about this idea, check out my newest barre videos – https://finisjhung.com/shop/ballet-barre-for-the-adult-absolute-beginner-2/ and https://finisjhung.com/shop/beginner-ballet-barre-2/

Concentrated work to develop this special plié is best done in the grand plié in a double-wide second position. Standing like this with feet far apart gives you a better idea of using energy that is equal and opposite.

Concentrated work to develop this special plié is best done in the grand plié in a double-wide second position. Standing like this with feet far apart gives you a better idea of using energy that is equal and opposite.

I tell the students that when they are preparing for the almost-isometric grand plié, they should resemble a triangle: the three points are the head, the right foot, and the left foot. Energy radiates outward from the center of the body through these three points. Energy up through the crown of your head resists the downward pull of your feet.

The almost-isometric plié begins at the floor. Your feet grip the floor in order to pull the legs into the plié position. Think of doing pull-ups when you are hanging from a barre; your elbows bend because you are pulling your body up. Or you can go to the wall barre and pull away from it (as you do my Kitchen Sink stretch). As you pull yourself toward the barre, your elbows bend. The almost-isometric plié works exactly like this.

In the upward movement of the almost-isometric plié, there is no deliberate “pulling up” of the body and straightening of the knees.

You relax your feet, spread your toes, and push down on the floor.

Think of doing a push-up on the floor. As you push the floor, your arms slowly straighten and bring your body up. In the same way, when you are in this plié, you press down on the floor and continue to do so until your legs return to the standing position.

Learning to do all of your pliés like this will build a path of energy from your toes to your head and enable you to move with power and grace.

Here are some important keys:

(To be continued. Excerpted from my book The Finis Jhung Ballet Technique: A Guide for Teachers & Students

Be sure to check out our Guidebook Packages

I think every plié should be done in such a way that it builds strength and balance. The only way that will happen is to make the muscles in the feet, legs, and body work.

In order to do this, you must eliminate the idea of assuming static positions and become more involved with the movement process.

How is it possible to move with maximum muscular involvement from a standing position with both knees straight to a plié position with both knees bent? How do you move with maximum muscular involvement from that plié to stand straight?

The answer is to use opposition. You will resist, or oppose, the movement. You will make your plié almost isometric. By definition, isometric means there is no movement. However, you are going to move into and out from a plié but in extremely slow motion, which is why I describe it as “almost-isometric.” You want to move so slowly and with such intensity that you don’t appear to be moving at all. But, you will certainly feel it happening with your muscles.

What makes the almost-isometric plié distinct is that there is no intentional or deliberate bending of the knees and lowering of the body into a static position. I tell my students, “Don’t make pictures when you dance. Don’t suddenly assume a position. Give me the movement. I want to see how you work into and out from the plié in slow motion. Give me the action. I want you to feel your muscles working.”

With an almost-isometric plié, you don’t want your body to go down; you don’t want your knees to bend. You don’t want to relax into a position.

(To be continued – Excerpted from my book – The Finis Jhung Ballet Technique: A Guide for Teachers & Students)

If you are going to pirouette, you usually begin from a plié in fourth or fifth position. If you are going to relevé to a pose, you begin with plié on one leg, or fondu. If you are going to jump, there’s a plié before and after. We can’t dance without the plié. The demi-plié initiates and completes almost every movement we make. Consequently, the plié is the most important and the most difficult movement to execute properly. The plié is ballet.

My first serious ballet teacher, Willam F. Christensen (affectionately called Mr. C.) often said, “You know, your legs bend, and they straighten. They bend, and they straighten. That’s it.”

How right he was. Adding on to Mr. C.’s straight talk, I teach pliés emphasizing how the legs bend and straighten. It is important for students to grasp the mechanics of the plié so that they will strengthen their feet, legs, and bodies as they work.

When you dance, you: 1. bend your knees so that you can /2. push the floor with your feet, which will / 3. cause you to either stand with a straight leg on a flat foot, on relevé, or leave the floor and spring up into the air as you / 4. execute a balance, turn, or jump.

We all want to have a plié that will power us strongly and safely as we begin and end our movements. With correctly executed pliés, we can dance with ease and avoid injuries to the feet, ankles, and knees. (To be continued) (Excerpted from The Finis Jhung Ballet Technique: A Guide for Teachers & Students)

If you are going to pirouette, you usually begin from a plié in fourth or fifth position. If you are going to relevé to a pose, you begin with plié on one leg, or fondu. If you are going to jump, there’s a plié before and after. We can’t dance without the plié.

The demi-plié initiates and completes almost every movement we make. Consequently, the plié is the most important and the most difficult movement to execute properly. The plié is ballet.

My first serious ballet teacher, Willam F. Christensen (affectionately called Mr. C.) often said, “You know, your legs bend, and they straighten. They bend, and they straighten. That’s it.”

How right he was. Adding on to Mr. C.’s straight talk, I teach pliés emphasizing how the legs bend and straighten. It is important for students to grasp the mechanics of the plié so that they will strengthen their feet, legs, and bodies as they work.

When you dance, you

We all want to have a plié that will power us strongly and safely as we begin and end our movements. With correctly executed pliés, we can dance with ease and avoid injuries to the feet, ankles, and knees. – To be continued. Excerpt from “The Finis Jhung Ballet Technique: A Guide for Teachers & Students”

Taught my adult absolute beginners tonight at the Ailey Extension to work their feet correctly and strongly: Sliding your foot out: heel, ball, toes press down and push the floor away to the pointe. Sliding your foot in: toes, ball, heel press down and drag the floor to the supporting foot. Your feet like to think and feel the floor

Your feet are never passive. They either stand, slide, roll to half-toe, or push off the floor. The supporting foot takes your weight and tells you when to move. The free foot leads the free leg to its position. Your feet have brains. Use them

Every movement you make should be powered by the action of your feet (or foot). In terms of preparing for the pirouette en dehors from the fourth position, keep the following in mind:

Excerpted from my book The Finis Jhung Ballet Technique: A Guide for Teachers & Students

Excerpted from my book The Finis Jhung Ballet Technique: A Guide for Teachers & Students

Why do we demi-plié? In order to spring up on half-toe or jump, and then to lower ourselves to the starting position. When you make a deep demi-plié with feet and legs relaxed you must then pull up out of the plié which will tend to set you back on your heels, make you fall off your turns, and lessen your elevation. You don’t need—or want—a deep, relaxed demi-plié—but you do need strong feet and ankles. Every movement we make comes from the floor. It begins with our toes and ends with our toes. In order to strengthen your feet and ankles, try to initiate your movements with an almost-isometric plié. I say “almost” because if it were simply isometric you would not move at all. Almost-isometric means that you move quietly and steadily with steely strength and intense opposition. The upward energy through the back of your neck equals the downward energy in your toes, feet, and ankles. Here’s how to learn what the almost-isometric plié feels like: Flatten both hands. Place one atop the other, palms down, fingers in opposite directions. Curl your fingers over each other. Grip strongly and pull as hard as you can without uncurling the fingers. Can you feel the muscles working in your fingers, hands, arms and shoulders? Now do this with your feet and legs. Stand in first position, grip the floor with toes curled and arches domed—you will feel your ankles tense—and slowly pull your knees into a small demi-plié. Resist the downward movement by stretching the back of your neck, keeping your hips as far from the floor as possible. The plié is minimal. Don’t lift your heels. You should feel a line of muscular engagement from your toes all the way up to your hips. Don’t think position; think power. Now you are ready to relevé: quickly press the balls of your feet against the floor, flatten your toes, and spring up to the half-toe. Keep driving your weight down through the floor until your legs are straight. Keep pushing your insteps over your spread toes. You should balance easily as long as you are in “Number 1” (correct posture). Try this with battement fondu en croix. Try it with a pirouette en dehors from both fifth and fourth positions. Yes, I know it is not in the ballet books. But we haven’t always had TV, the internet, and hip and knee replacements. Times have changed. So should you. This is explained in detail in my instructional video “Ballet Barre for the Adult Absolute Beginner” which is available on my website and Amazon.

Why do we demi-plié? In order to spring up on half-toe or jump, and then to lower ourselves to the starting position. When you make a deep demi-plié with feet and legs relaxed you must then pull up out of the plié which will tend to set you back on your heels, make you fall off your turns, and lessen your elevation. You don’t need—or want—a deep, relaxed demi-plié—but you do need strong feet and ankles. Every movement we make comes from the floor. It begins with our toes and ends with our toes. In order to strengthen your feet and ankles, try to initiate your movements with an almost-isometric plié. I say “almost” because if it were simply isometric you would not move at all. Almost-isometric means that you move quietly and steadily with steely strength and intense opposition. The upward energy through the back of your neck equals the downward energy in your toes, feet, and ankles. Here’s how to learn what the almost-isometric plié feels like: Flatten both hands. Place one atop the other, palms down, fingers in opposite directions. Curl your fingers over each other. Grip strongly and pull as hard as you can without uncurling the fingers. Can you feel the muscles working in your fingers, hands, arms and shoulders? Now do this with your feet and legs. Stand in first position, grip the floor with toes curled and arches domed—you will feel your ankles tense—and slowly pull your knees into a small demi-plié. Resist the downward movement by stretching the back of your neck, keeping your hips as far from the floor as possible. The plié is minimal. Don’t lift your heels. You should feel a line of muscular engagement from your toes all the way up to your hips. Don’t think position; think power. Now you are ready to relevé: quickly press the balls of your feet against the floor, flatten your toes, and spring up to the half-toe. Keep driving your weight down through the floor until your legs are straight. Keep pushing your insteps over your spread toes. You should balance easily as long as you are in “Number 1” (correct posture). Try this with battement fondu en croix. Try it with a pirouette en dehors from both fifth and fourth positions. Yes, I know it is not in the ballet books. But we haven’t always had TV, the internet, and hip and knee replacements. Times have changed. So should you. This is explained in detail in my instructional video “Ballet Barre for the Adult Absolute Beginner” which is available on my website and Amazon.