I think every plié should be done in such a way that it builds strength and balance. The only way that will happen is to make the muscles in the feet, legs, and body work.

In order to do this, you must eliminate the idea of assuming static positions and become more involved with the movement process.

How is it possible to move with maximum muscular involvement from a standing position with both knees straight to a plié position with both knees bent? How do you move with maximum muscular involvement from that plié to stand straight?

The answer is to use opposition. You will resist, or oppose, the movement. You will make your plié almost isometric. By definition, isometric means there is no movement. However, you are going to move into and out from a plié but in extremely slow motion, which is why I describe it as “almost-isometric.” You want to move so slowly and with such intensity that you don’t appear to be moving at all. But, you will certainly feel it happening with your muscles.

What makes the almost-isometric plié distinct is that there is no intentional or deliberate bending of the knees and lowering of the body into a static position. I tell my students, “Don’t make pictures when you dance. Don’t suddenly assume a position. Give me the movement. I want to see how you work into and out from the plié in slow motion. Give me the action. I want you to feel your muscles working.”

With an almost-isometric plié, you don’t want your body to go down; you don’t want your knees to bend. You don’t want to relax into a position.

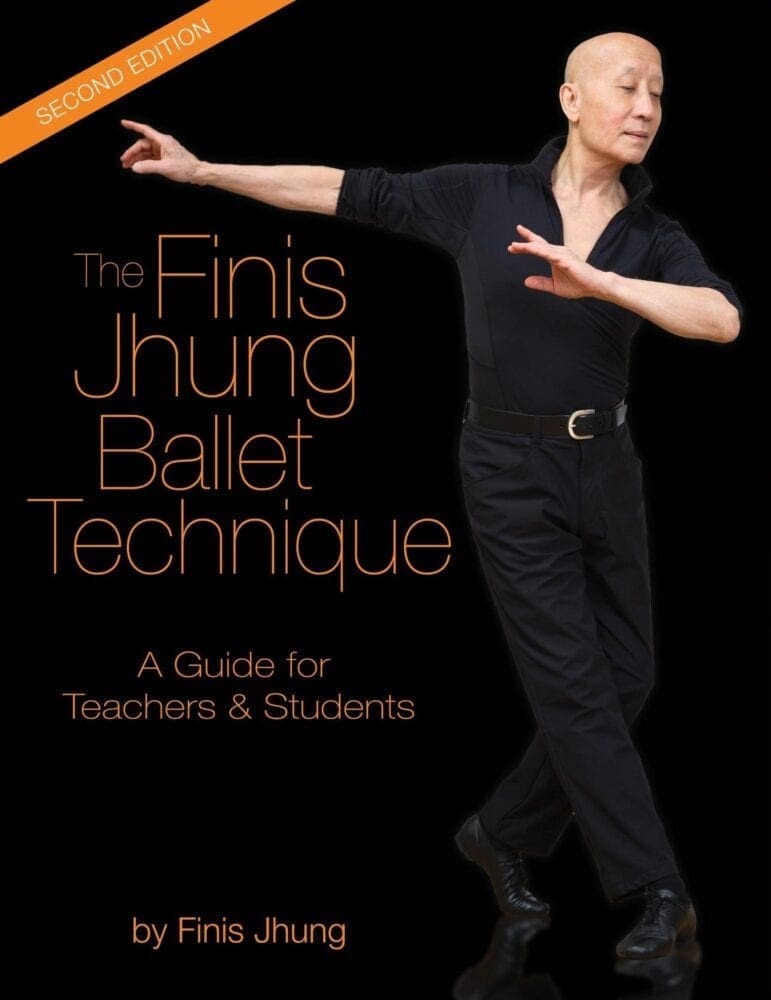

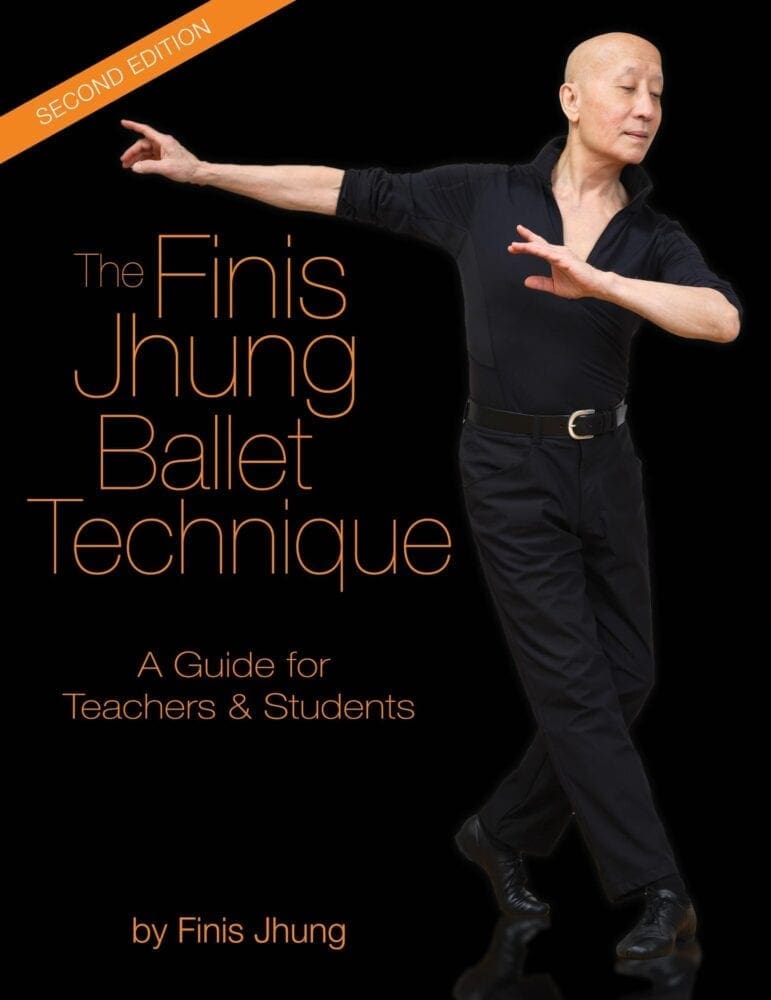

(To be continued – Excerpted from my book – The Finis Jhung Ballet Technique: A Guide for Teachers & Students)